Does a book from 1840 really say don't discuss religion or politics?

I was curious about the origin of the saying, "Never talk about politics or religion in polite company." One of the oldest references that came up on Google was The Letter Bag of the Great Western (1840) by Thomas Chandler Haliburton. I needed to track down this book and I was in luck: there was a copy at the Toronto Reference Library in the Baldwin Collection of Canadiana. I went down a serious rabbit hole that day. Let me tell you about the best bits.

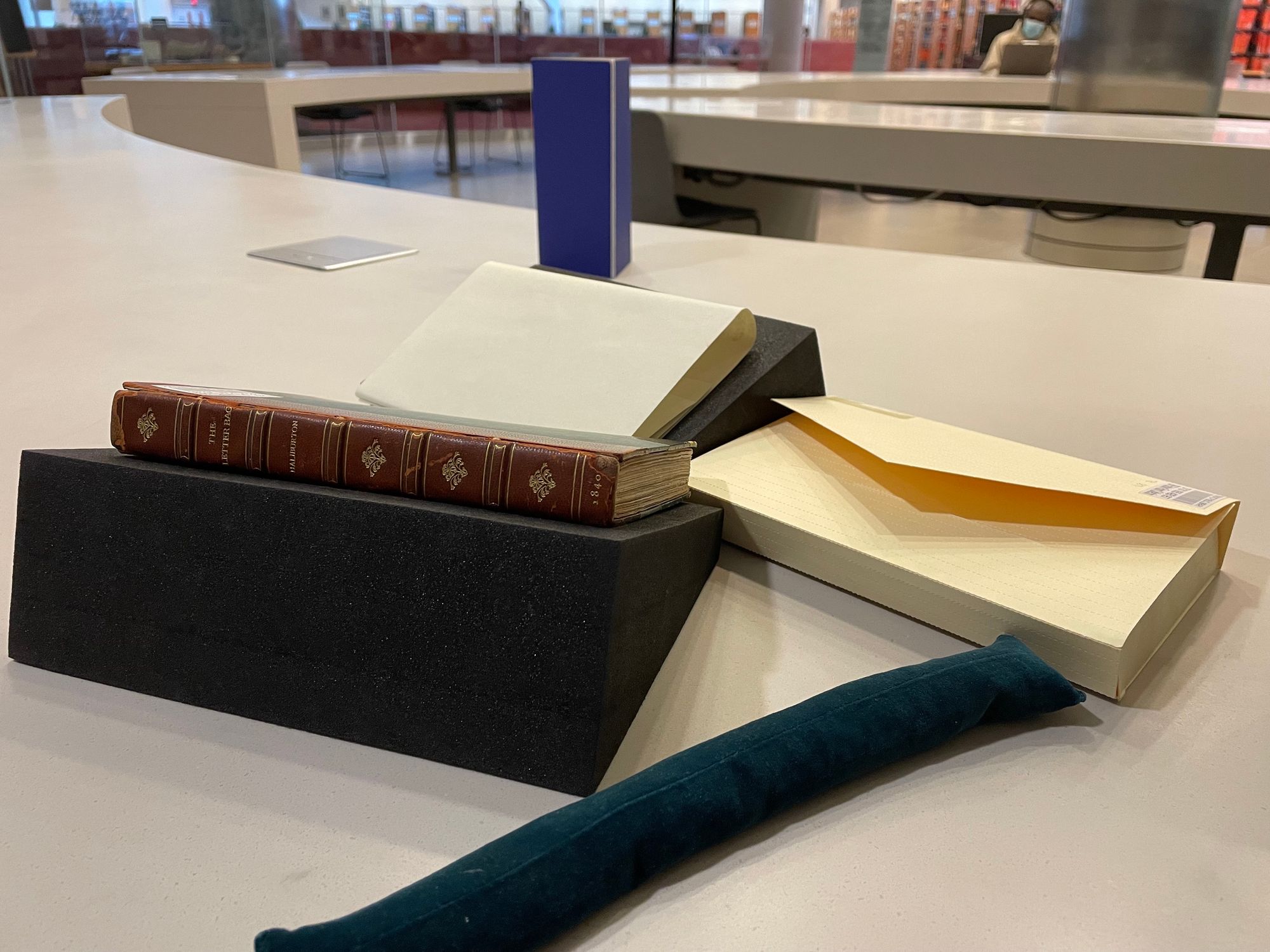

The Baldwin Collection is part of the rare book collection, housed in its own room within the library. When I entered Marilyn & Charles Baillie Special Collections Centre, I had to register to use the space. The librarian helped me fill out a request for the book. Then, I waited in the tranquil rotunda for a staff member to bring it to me.

The outermost layer was a slipcover, a custom-made box for the book fashioned from heavy card stock. The next layer was a book jacket. The book itself was bound in red leather. It had previously been re-bound, so the original spine and front cover were included at the end of the book.

The librarian provided a foam book cradle, so I could have the book open without damaging the spine. She also provided a book weight, a long bean bag for holding the book open gently. Even with these precautions, there were quite a few crumbs of leather on the desk by the time that I was done.

I did not have to wear gloves to handle the book. I could use only a pencil (no pens!) to take notes and I was not allowed to eat or drink.

Each chapter of The Letter Bag of the Great Western was a letter from a passenger aboard the ship. The book was... puzzling. The diction and sentence structures were foreign, not surprising given the 180 years between me and the author. But it was odd in other ways too.

For example, the book dedicated the Right Honourable Lord John Russell, who was Prime Minister of Britain at the time. Although the author didn't know the Prime Minister, he included the tribute to make the book more marketable. He wrote:

All the world will say that is in vain for the Whig ministry to make protestations of regard for the colonies, when the author of that lively work "The Letter Bag of the Great Western," remains in obscurity in Nova Scotia, languishing in want of timely patronage, and posterity, that invariably does justice (although it is unfortunately rather too late always) will pronounce that you failed in your first duty, as protector of colonial literature, if you do not do the pretty upon this occasion.

In the Preface, the author breaks the fourth wall and doesn't tell us how he came into the possession of private mail.

The obvious inference is, I confess, either that the postmaster-general has been guilty of unpardonable neglect, or that I have taken a most unwarrantable liberty with his letter bag. Under these circumstances, I regret that I do not feel myself authorized, even in my own justifications, to satisfy the curious reader...

I needed more context to make sense of this book.

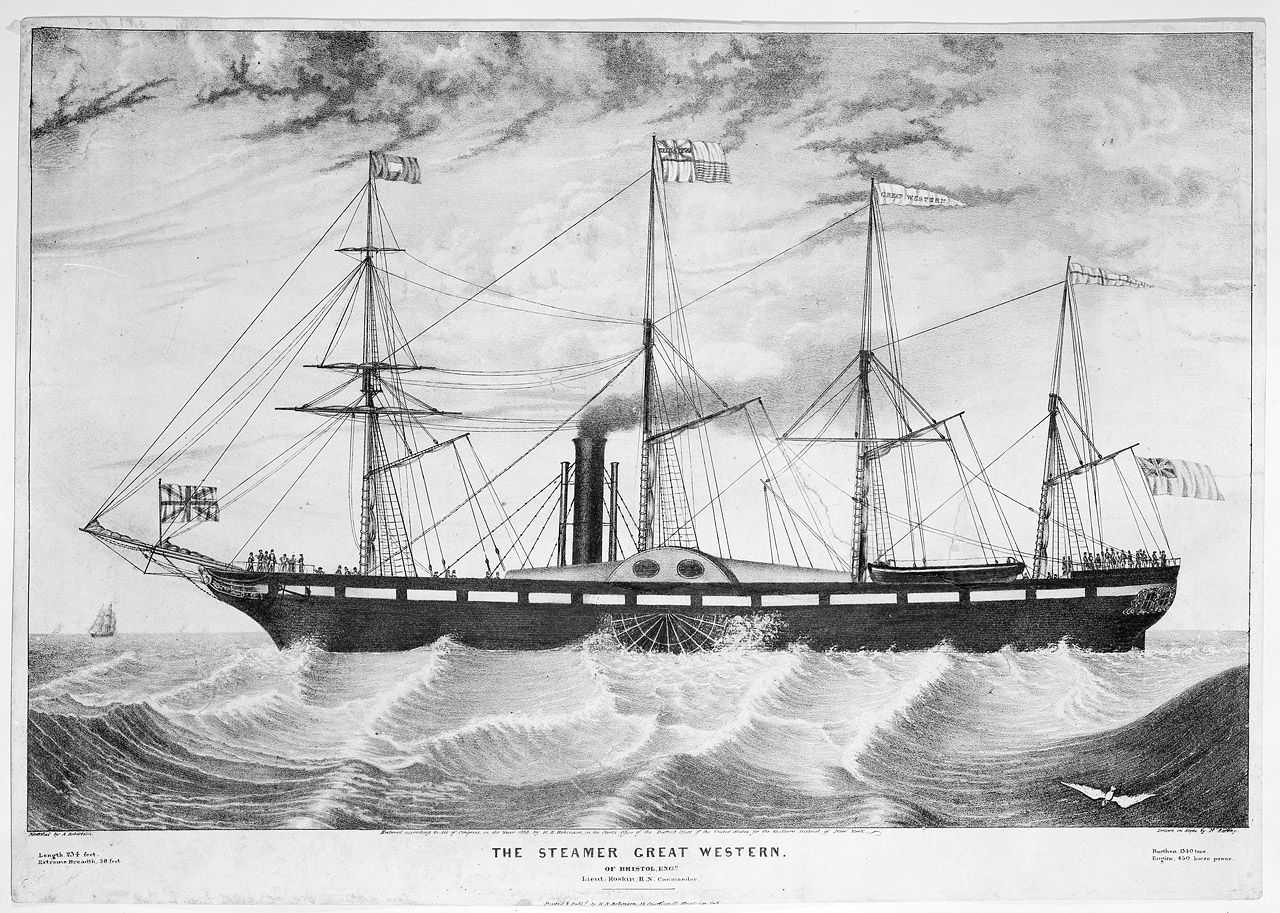

SS Great Western was a wooden hulled, paddle steamer that was built for the purpose of making regular crossings between Bristol and New York.

The ship was large– dangerously large, critics contended– so the crossing would be fuel efficient. It displaced 2300 tons, and was 76.8m long and 17.59m wide across the wheels. It was capable of carrying 120 passengers, 20 servants, and a crew of 60. Between 1838 and 1856, the Great Western crossed the Atlantic Ocean 45 times. The westward crossing would take 16 days and the reverse trip took about 13.4 days.

Sidebar: There was subsequently an even larger ship named SS Great Eastern, built to make regular journeys to Australia. There was a CBC radio series of the same name that purported to be aired by the Broadcasting Corporation of Newfoundland.

The author was Thomas Chandler Haliburton. He was born in Nova Scotia in 1796 and died in England in 1865. He was the first Canadian-born author to gain international renown, which is why the library had this book in their collection. Haliburton was a lawyer, judge, and member of the Nova Scotia Legislative Assembly. When he retired from law, he moved to England and while he was there he became a Member of Parliament.

Haliburton wrote both fiction (satirical sketches) and non-fiction (reports on life in Nova Scotia).

The pieces fell into place when I realized that The Letter Bag of the Great Western was a work of satirical fiction, which is completely consistent with other work by Haliburton.

This bit of insight meant that I needed to look at the suggestion to not talk about politics or religion in a different light.

The relevant letter is from "John Stager" and titled "Letter from an Old Hand." It gives 18 tips on how to live one's best life on the ship. To illustrate, here is Tip #1.

1st. Call steward, inquire the number of your cabin; he will tell you it is No. 1, perhaps. Ah, very true, steward; here is half a sovereign to begin with; don't forget it is No. 1. This is the beginning of the voyage, I shall not forget the end of it. He never does lose sight of No. 1, and you continue to be No. 1 ever after; –best dish at dinner, by accident, is always placed before you, best attendance behind you, and so on. You can never say with the poor devil that was hen-pecked, "The first of the tea and the last of the coff-ee for poor Jerr-y." –I always do this.

This is sassy writing. One can imagine this tip as part of a Mr. Bean skit or perhaps a Borat movie.

Let's now turn to Tip #12, which mentions politics and religion, and was the original reason for tracking down this book

12th. Never discuss religion or politics with those who hold opinions opposite to yours; they are subjects that heat in handling until they burn your fingers. Never talk learnedly on topics you know, it makes people afraid of you. Never talk on subjects you don't know, it makes people despise you...

This advice is impossible to follow. How do you learn that someone holds opinions different from yours without engaging in discussion? If you can never talk about subjects you know nor subjects you don't know, what is left?

Haliburton is satirizing conventional etiquette. As a legislator, he no doubt had many conversations about politics. Even the dedication of The Letter Bag of the Great Western was a political gesture.

A couple of inferences can be made here. One, in 1840 the adage to never discuss politics or religion is sufficiently well known that it can be satirized. Two, the saying is worthy of being mocked, as if one can't seriously suggest it or follow it.

And yet two centuries later, we have Miss Manners, lawyers, a business blogger, and others giving this advice seriously.

I'm going to keep digging, both backwards and forwards in time. Where did this adage come from? And what is it doing to us now?

The day spent at the Toronto Reference Library was a pleasure. There were so many books; if only we could learn from them through osmosis. It felt like time travel to touch a book that was published so long ago. It's an inclusive space that requires neither money nor a library card for admission. It's quiet and the librarians are here to help. The bathrooms are clean, with burly paper towels that actually dry your hands, and sharps disposal units. I'm thankful that when so much of the city feels like it is coming undone due to underfunding, we still have this oasis of knowledge and dignity.